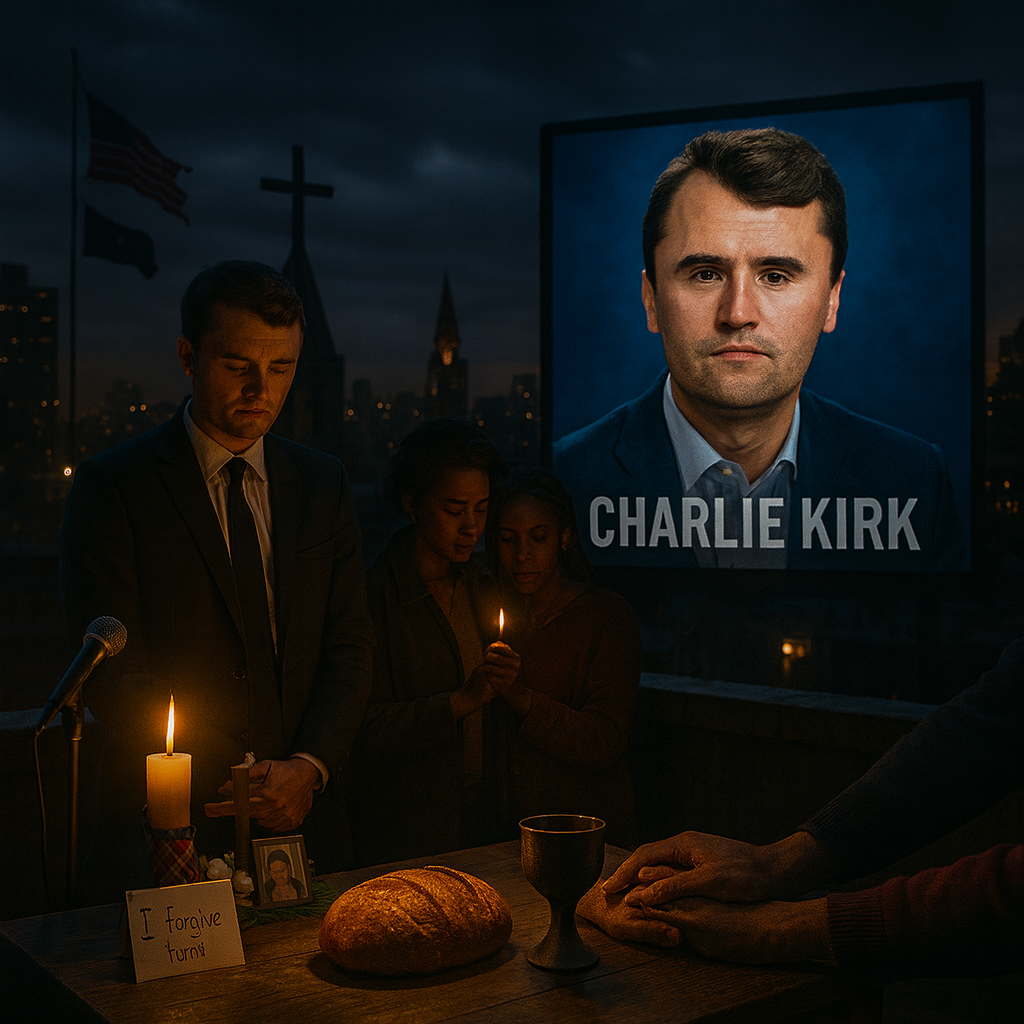

On September 10, 2025, a rooftop gunman killed Charlie Kirk as he spoke at Utah Valley University. Police named Tyler Robinson as the prime suspect, 22, arrested after a 33-hour manhunt; prosecutors say the attack was premeditated and politically motivated, and they intend to seek the death penalty. Court filings cite texts, a note, and family statements indicating resentment at Kirk’s rhetoric and a leftward political turn; Robinson has obtained capital-defense counsel as evidence review proceeds.

America’s right split in its response. At Kirk’s stadium memorial in Arizona, Erika Kirk stunned the country with three words—“I forgive him”—a distinctly Christian act that refuses both denial of evil and the lust for revenge. Donald Trump honored Kirk but framed the murder as a battle with the “radical left.” Stephen Miller delivered a rousing, us-versus-them call—“we will prevail over wickedness”—that critics called a political rally inside a funeral. Tucker Carlson, by contrast, said the solution is Jesus, not ideology.

America’s left wasn’t monolithic either. Prominent Democrats publicly condemned political violence and urged de-escalation; youth leaders from College Democrats and Republicans even issued a joint statement on nonviolence. Yet progressive feeds also featured mockery of Kirk and calls to focus on guns and rhetoric rather than ideology alone—while some outlets criticized Trump’s response as inflaming division.

Even the entertainment sphere fractured: Jimmy Kimmel drew a suspension over remarks, then returned tearfully to say he hadn’t meant to trivialize the killing—an emblem of a media system that can’t decide whether these moments require sobriety, satire, or sides.

The Deeper Disquiet: Why This Death, and Why Now?

Why did one assassination of a celebrity podcaster dominate Western feeds when thousands of Christians are being murdered, kidnapped, or terrorized in Nigeria and the DRC—killings many Americans never hear about? Reports this year alone speak of thousands of Christian deaths and abductions in Nigeria, priests targeted and churches destroyed; Islamic State–linked militias have slaughtered worshippers in the DRC, including funeral and church attacks with mass fatalities.

That asymmetry of attention is not just a media problem; it’s a meaning problem. A society without a shared account of truth will amplify the spectacular and ignore the systemic; it will convert grief into content and suffering into narrative fuel for the next culture-war turn.

So let’s ask the only question that can discipline our reactions:

What if ultimate truth actually exists?

If it does, how does that truth render this murder intelligible—its evil, its judgment, its possibility of forgiveness? How does it address the obvious vacuum in post-modern life—where relativism births nihilism—and how does it answer the heart’s ache for transcendence without pretending technology can engineer it?

Two temptations offer counterfeit answers:

- Post-modern secularism tells us truth is a construct; the result is an epidemic of meaninglessness—alienation, identity crises, despair.

- Techno-eschatology (the thrust of Peter Thiel’s recent private lectures on the Antichrist) rightly sees the hunger for transcendence but tries to force it into history—fusing ontological longing with technology, capital, and code. That bridge can’t hold: finite tools cannot bear infinite hope.

Both secular relativism and technological salvation are this-worldly substitutes for transcendence. They misdiagnose the human condition. Which is why the most jarring moment at the memorial wasn’t the political rhetoric, but Erika’s forgiveness: it announced, against the grain of the age, that Truth is personal and mercy is not amnesia.

2. Christianity is Antithetical to Nationalism

The reflex to frame Charlie Kirk’s murder as a call for Christian nationalism reveals a fundamental confusion. It treats Christianity as an instrument of tribal consolidation rather than as an ontological claim about reality. But Christianity is precisely the opposite of nationalism.

The apostles, the men who knew Jesus, had every incentive to defect after His crucifixion. They had lost trades, homes, social status. They faced persecution, exile, imprisonment, martyrdom. Game theory suggests that if they had been in this for power, they would have acted like Judas — cutting their losses. Instead, they chose costly persistence. They proclaimed a universal gospel that broke tribal boundaries: Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female — all one in Christ Jesus.

Nationalism, by contrast, is about status, power, and control within the bounded frame of a tribe or state. It seeks security by mobilizing identity against outsiders. Christian nationalism is therefore a contradiction: it exchanges the ontology of truth for the praxis of power. It is a “status game” in religious dress, not unlike the ideological projects of the twentieth century.

The contrast was visible at Kirk’s memorial. Erika’s forgiveness was ontological — it enacted the truth that Jesus is Lord, that mercy is real. Tucker Carlson’s call to return to Jesus rather than ideology pointed in the same direction. But Stephen Miller’s fiery mobilization speech, Trump’s us-versus-them rhetoric, and the online calls for Christian nationalism revealed how quickly grief can be transmuted into a culture-war status play.

Christianity is bound to offend all alternative ontologies — paganism, secularism, Islam, technognosticism — because it claims an absolute truth in Christ. But the offense is not meant to come through political conquest or cultural militancy. It is meant to come through the counter-cultural life of the church: forgiveness in the face of hatred, purity in the face of decadence, steadfastness in the face of persecution. The apostles did not win the first century by winning elections; they won by living lives of holiness and truth, even unto death.

3. A Unified Test Framework for Truth Claims

If Charlie Kirk’s murder has exposed the fragility of our cultural narratives, it also provides an occasion to ask a deeper question: Which system of belief actually holds up under the weight of history and rational stress-testing? To answer that, we need a single framework that treats every system the same way.

The framework we use here has three layers:

- Game theory — Do the incentives align with defection, or does costly persistence dominate?

- Network effects — How does the belief system diffuse: by patronage, coercion, myth-accretion, or antifragile growth under persecution?

- Bayesian stress testing — When all evidence nodes are weighed (adversarial conversions, mass-witness claims, creed formation, costly persistence, diffusion pattern), which hypothesis best explains the data?

Applied neutrally, without privileging one tradition over another, here is what emerges:

Christianity

The apostles had every incentive to abandon the movement after Jesus’ crucifixion. Instead, they endured persecution, exile, and death. Paul, its fiercest adversary, became its greatest evangelist. A mass-witness claim (the “500” in 1 Corinthians 15) anchored the testimony. Within decades, creeds and hymns were circulating across diverse communities. Crucially, Christianity spread without state power for centuries, and its diffusion actually intensified under persecution.

- Game theory: defection incentives ignored; costly persistence dominates.

- Network effects: antifragile growth under persecution, not coercion.

- Bayesian stress test: posterior for an extraordinary catalyst clears 99% unless one assumes a prior against the resurrection smaller than one-in-a-billion.

Judaism

Validated by its antiquity, national memory, and the Sinai theophany. Costly persistence over millennia (pogroms, exiles, Holocaust) is unparalleled. But Judaism is deliberately non-expansionary: it sustains identity, not global diffusion.

- Game theory: costly persistence holds.

- Network effects: tribal-national, not universal.

- Bayesian stress test: plausible signal for divine origin, but posterior depends heavily on starting priors. Functions best as precursor to Christianity.

Islam

Emerges in the 7th century with a rapid codification of text and creed. Early expansion was dramatic but tethered to state-building and military conquest. Diffusion correlates with political patronage and power consolidation.

- Game theory: incentives align with joining victors, not enduring persecution.

- Network effects: spread by sword, empire, patronage.

- Bayesian stress test: favors naturalistic models.

Buddhism & Hinduism

Both have vast cultural depth, but their spread was tied to imperial patronage (Mauryan, Gupta, Chinese dynasties). Their canons evolved slowly over centuries. No mass-witness claim anchors their origins.

- Game theory: persistence via cultural absorption, not martyrdom.

- Network effects: diffusion by empire and cultural osmosis.

- Bayesian stress test: naturalistic explanation sufficient.

Modern Ideologies (Communism, Liberalism)

Explained by material incentives, propaganda, and state power. Their rise and fall correlate with institutions, not divine encounters.

- Game theory: persistence incentivized by state enforcement.

- Network effects: diffusion tracks institutions, schools, armies, and economies.

- Bayesian stress test: entirely naturalistic.

Cults and NRMs

Benign cults scale only within small networks; coercive cults scale by manipulation, fear, and control. Neither produce large-scale antifragile growth absent patronage.

- Game theory: persistence explained by social pressure.

- Network effects: limited or coercive.

- Bayesian stress test: strongly naturalistic.

The Result

When all systems are tested on the same field, the outcome is stark:

- Only Christianity produces a convergence of signals that naturalistic explanations cannot account for: costly persistence against incentive, adversarial conversions, mass-witness claims, rapid creed formation, antifragile diffusion without state power.

- Judaism emerges with partial validation as a necessary precursor to Christianity, confirming the prophetic arc.

- All others collapse into naturalistic categories — power, patronage, coercion, or cultural osmosis.

Christian nationalism fails this test as well. It is not Christianity itself but a cultural-political project. It seeks to re-anchor faith in the very categories the framework exposes as naturalistic: status, control, patronage, coercion. To trade ontology for praxis is to surrender truth for power — precisely what the apostles rejected and precisely what Jesus refused when offered the kingdoms of the world.

3.1 Testing Truth Claims

The value of a single testing framework is that it forces every system — Christianity, Judaism, Islam, ideologies, cults — onto the same field of play. The method is straightforward:

- Game theory: do incentives favor persistence or defection?

- Network diffusion: is spread explained by patronage, coercion, or antifragility under persecution?

- Bayesian stress testing: how do the observed data shift posterior probabilities under naturalistic versus extraordinary-catalyst hypotheses?

Christianity and the Mathematics of Weakness

When we formalize Christianity’s evidential profile, we assign likelihoods to each evidence node under two top-level hypotheses:

- R (Resurrection / extraordinary catalyst)

- NAT (model-averaged naturalism): fabrication, hallucination, myth, or purely sociological explanations

The evidence set includes the standard historical anchors — costly persistence (E1), Paul’s adversarial conversion (E2), the “500” mass-witness claim (E3), antifragile spread without state power (E4), and early creedal stability (E5).

But we must also add E6: the scandal of the Cross. In the Greco-Roman honor/shame world, the very idea of a crucified deity was anti-memetic. A God who not only dies but dies shamefully — and then refuses immediate vengeance, promising judgment only at His return — was foolishness to Greeks (1 Cor 1:23). This weakness should have killed the movement. Yet it did not. It spread. That inversion of expectations itself becomes powerful evidence.

Worked Example: Conservative Calibration

Let’s assign conservative means for each evidence node:

Naïvely multiplying gives \prod \text{BF}_i \approx 2.3 \times 10^5.

But to avoid double-counting, apply a dependence penalty \delta = 0.6:

\log \text{BF}_\text{total} = 0.6 \sum_i \log \text{BF}_i

Result: \text{BF}_\text{total} \approx 1.3 \times 10^3.

The skeptical prior boundary (SPB) — the prior needed to keep the posterior at 50% — is then:

p^\star = \frac{1}{1+\text{BF}_\text{total}} \approx 7.5 \times 10^{-4}.

Even with strict penalties, you’d need to start with a prior smaller than 0.08% against the resurrection to avoid being pushed over 50%. If we relax to \delta=0.8, the BF rises to 2 \times 10^4, lowering the SPB to ~5 \times 10^{-5} — one-in-twenty-thousand.

Why the “Foolishness” Becomes Evidence

- In a world where gods were heroes, generals, and emperors, a crucified God was madness.

- Even with a resurrection claim, deferred vengeance — no thunderbolts, no immediate justice — undermined Greco-Roman religious expectations.

- Converts gained no material payoff: a slave who believed remained a slave, still vulnerable, still disregarded by society.

- Yet precisely this message spread, and in time erased millennia of Greek and Roman religion.

Naturalistic models predict extinction of such an anti-meme. The observed spread is far more probable under R. The very “weakness” that should have killed Christianity becomes its strongest signal.

Game Theory and Diffusion Recap

- Payoff structure: defecting (like Judas) was rational under NAT; persisting was ruinous. Apostolic coordination on persistence only makes sense if an overwhelming catalyst inverted the payoff table.

- Network effects: without state power, NAT predicts R_0 < 1 and extinction. With R, conviction stabilizes growth despite shocks. Early Christianity’s antifragility is therefore a decisive likelihood divider.

Conclusion of the Test

Christianity alone clears the evidential bar, even under skeptical settings. Judaism retains a partial signal as precursor; all others collapse into naturalistic categories. And crucially: Christian nationalism fails this same test, because it swaps Christianity’s ontology of costly truth for a praxis of worldly power. That is not how the faith began, and it is not how it endures.

3.2. The Same Framework Applied to Political Ideologies

To confirm that this framework is not special pleading for Christianity, we must also test it on modern political ideologies. The categories remain the same: game theory, network effects, and Bayesian stress testing. The only adjustment is the evidential nodes, which map into ideological rather than religious terms.

Communism

- Game theory: Early communists endured costs before 1917, but adoption skyrocketed only after state capture. Costly persistence is explained by grievances and networks rather than transcendent claims.

- Network effects: Scaling is tightly coupled to coercion and patronage. Defections are common once costs rise and state control weakens.

- Bayesian stress test: Assigning conservative probabilities yields Bayes factors well below 1. The data are more probable under NAT than under any extraordinary-catalyst hypothesis.

- Interpretation: Communism spreads like an ideology of power, not like a truth-bearing ontology.

Democratic Liberalism

- Game theory: Early advocates like Locke and Montesquieu faced pushback, but diffusion mostly tracked merchant and institutional interests. Payoffs generally aligned with adoption, not costly defection.

- Network effects: Diffusion spreads with trade, empire, and constitutional adoption. There is no antifragility under persecution; rather, uptake follows incentives.

- Bayesian stress test: As with communism, the aggregate Bayes factor is <1. The system fits naturalistic diffusion.

- Interpretation: Liberalism spreads as institutional praxis, not as ontological revelation.

What the Comparison Shows

The same framework that exposes Christianity as ontologically grounded also explains why ideologies succeed or fail.

- Christianity spreads through anti-memetic weakness and antifragility under persecution — a profile that NAT cannot explain.

- Ideologies spread through patronage, coercion, and incentives — a profile fully consistent with NAT.

This comparison matters because it demonstrates the test is generalizable: it classifies social systems by how they behave under incentives, networks, and evidential load. Christianity uniquely clears the bar; Judaism partly clears it as precursor; ideologies, cults, and other religions do not.

And here is the pivot: Christian nationalism fails this very test. It abandons Christianity’s ontology of costly truth for the praxis of political status. In doing so, it behaves like an ideology — explained by NAT, not by revelation.

3.3. When Christianity Collapses into Ideology

3.3 When Christianity Collapses into Ideology

Christianity becomes ideology the moment a Person is displaced by a program. When Jesus Christ crucified and risen no longer governs the center, a policy horizon or movement identity quietly takes His seat. The swap is subtle—usually presented as prudence or compassion—but its fruits are legible. Incentives become cheap; growth depends on patronage and algorithmic reach; doctrine flexes to fit coalition needs. Under the same test we have applied throughout—game theory, network diffusion, and Bayesian stability—what looks like renewal reveals itself as naturalistic imitation of faith.

By Christian nationalism I mean the attempt to fuse covenant loyalty to Christ with civil authority and national identity, treating the state as ordinary guarantor of Christian ends. By Christian liberalism I mean the reframing of the faith as a moral engine for progressive inclusion within the civic horizon of liberal democracy. Both begin with recognizably Christian motives—order and holiness in the first case; mercy and justice in the second. Both become ideological when the good they prize is severed from the Giver and re-anchored in coalition maintenance.

Viewed through incentives, the difference is stark. Where Christ remains the center, communities absorb real costs: they tell the truth when it shrinks the crowd, reconcile enemies when it scandalizes friends, and hold creeds steady when donors flinch. Where a program rules, allegiance is subsidized and costly persistence evaporates. In nationalist forms, holiness is measured by boundary-policing and bloc discipline; in liberal forms, kindness is measured by affirmation and policy alignment. Either way the game-theoretic profile shifts: martyr-logic fades, and compliance with the coalition becomes rational.

The diffusion pattern follows. Churches centered on Presence prove antifragile: they do not require media prestige, legal shelter, or institutional access to endure. But once Christianity is instrumentalized, growth maps neatly to patronage—broadcast platforms, money, law, and cultural approval. Remove those supports and the witness withers. This is why both projects, despite opposite rhetoric, leave signatures that our framework classifies as naturalistic diffusion rather than ontological surprise.

The Bayesian update then exposes what has moved in the center. Where Christ and Him crucified governs, creeds, sacraments, and enemy-love persist even when politically disadvantageous; the likelihood of such stability is high under the resurrection hypothesis and low under model-averaged naturalism. Where a program governs, doctrines most resisted by the zeitgeist are softened first; other doctrines are weaponized when they mobilize the base. The posterior drifts toward NAT not because anyone declares unbelief, but because the evidential bundle now behaves like ideology.

None of this requires caricature. The love of place, the pursuit of just laws, the defense of the weak—these are real goods. National service, order, and cultural continuity deserve gratitude; advocacy, hospitality, and institutional reform deserve effort. The critique lands only when these goods govern the church’s center instead of being governed by it. Instrumentalization is the common failure mode. Scripture becomes a quarry for talking points rather than God’s testimony to the Son; identity is secured by negation (“we are not them”) rather than by communion; what cannot be said grows each year because the coalition cannot bear it.

The path back is not a clever synthesis of left and right but re-mooring. The table disciplines the feed: enemies reconcile before they opine. Catechesis disciplines coalitions: creeds set the edges and coalitions must fit the creed, never the reverse. Holiness is restored as presence rather than performance, so discipline aims at communion rather than spectacle. Kindness is restored as cruciform love rather than sentiment, so truth-telling is not traded for approval and justice is not weaponized for vengeance. Leaders speak plainly about costs—votes, donors, acclaim—and accept them without panic because the church’s future does not depend on favorable algorithms.

In summary: Christian nationalism and Christian liberalism begin with Christian goods but end by collapsing the gospel into outcomes—sovereignty or inclusion. On the shared field of incentives, networks, and posterior stability, both register as naturalistic diffusion: allegiance is low-cost, growth is patronage-sensitive, and doctrine bends to the bloc. The apostolic pattern differs in kind. It remains antifragile under loss, centers on the scandal of the Cross, and keeps producing a people whose holiness and kindness are fruits of Presence rather than tools of power. Programs can align behavior; they cannot make new creatures. Only a crucified and risen Lord does that.

The Shared Problem

Though they present as opposites, Christian nationalism and liberal Christianity are mirror images. Both trade ontology for praxis. Both reduce the church’s transcendent witness to a social ideology that NAT can fully explain. Both erode the scandal of the Cross, the costly persistence of the apostles, and the radical claim that Jesus Himself is truth.

The early church did not die for political opinions — it died for a person. The gospel is not a program for social power but the announcement that the crucified God has risen, and that this truth overturns every other claim. That truth cannot be co-opted as an appendage to tribal identity or to liberal progressivism without ceasing to be itself.

Conservatism cannot be more righteous than God. The measure of divine hatred for sin is not a stricter policy platform but a crucifixion: “God so loved the world…that He gave His Son.” Holiness defined by coalition will always drift toward performance and punishment; holiness defined by Calvary exposes sin more absolutely than any culture war ever could, because it judges all—right and left—at the wood of the cross. There the verdict falls on Christ in our place. Moral absolutism apart from Christ is therefore hollow: it condemns without atonement, disciplines without adoption, and polices boundaries without the Spirit’s power to make new creatures. God’s righteousness is not a cudgel we wield; it is a sentence He bore. And because He bore it, repentance is not a partisan weapon but the doorway to life.

Likewise, liberalism cannot be more merciful than God. The measure of divine mercy is not inclusion by sentiment but inclusion by substitution: the Son gives Himself for us and to us. Mercy without the cross dissolves into curation; “welcome” without repentance becomes a managed vibe. The gospel’s welcome is infinitely wider and infinitely costlier: God’s arms extend to the ends of the earth—but they extend on a cross. Thus inclusion apart from atonement is delusion, because it refuses the very surgery that heals. The church does not lower truth to raise compassion; in Christ, truth goes down into death to raise sinners into communion. The invitation is universal, but it honors the price: He died for us—therefore we must turn to Him.

This is why the cross collapses all partisan pretensions. God is more horrified by human wickedness than any conservative platform can articulate—and His remedy is not cultural dominance but the death of His Son, vindicated by resurrection. God is more tender toward the crushed than any progressive manifesto can imagine—and His remedy is not sentiment, but the same cross that calls every guest to repentance and new birth. Christian love outstrips progressivism because it is cruciform: since Jesus loved us to death, Christians must love one another—and even enemies—with a willingness to spend and be spent. Christian holiness outstrips conservatism because it faces eternal judgment without flinching: “the soul that sins shall die,” and only Christ can save. At the cross every ideology breaks; only Christ remains.

And this is not mere rhetoric. The crucifixion and the empty tomb are not decorative symbols; they are the constraintsour analysis keeps rediscovering. Under the shared rules—costly persistence, antifragile diffusion, stable creed, adversarial conversion—the resurrection keeps winning the update. That empirical stubbornness is the warrant for the moral absolutes and the radical mercy named above: both flow from events in history, not wishes in a tribe. Hence the church’s center is fixed where math and witness meet—at a cross that condemns our pride and a tomb that won’t stay shut.

3.4. The Historical Pattern of Co-opted Christianity

What we are describing is not an abstract risk but a repeated historical reality: when Christianity is co-opted by political elites, its transcendent ontology is diluted into a tool for social power. The witness of the church is eclipsed, and the framework we have used classifies the resulting behavior squarely as naturalistic ideology, not divine truth.

The Roman Empire

By the fourth century, Christianity’s growth had become undeniable. Constantine’s conversion and the Edict of Milan (313 AD) ended persecution — a profound historical shift. But incorporation into imperial machinery quickly made Christianity a political utility. Orthodoxy became entangled with loyalty to the emperor, bishops gained state-backed authority, and heresy trials became tools for political consolidation. Christianity traded its early antifragility for state patronage; ontology gave way to praxis.

European Monarchies and Christendom

Medieval kings and queens wielded Christianity as a legitimizing crown. Dynastic conflicts between “Christian” nations spilled rivers of baptized blood. The Wars of Religion in early modern Europe — Catholic versus Protestant — saw Christians killing Christians under banners of orthodoxy, though the deeper logic was often dynastic and territorial power. Even the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), often cast as confessional, was fueled as much by Habsburg–Bourbon rivalry as by theology.

The Crusades

Launched ostensibly to reclaim the Holy Land, the Crusades reveal the power-political layer beneath the rhetoric. While many crusaders were sincere, the campaigns often pursued wealth and land. The sack of Constantinople in 1204, where crusaders turned on fellow Christians, is a vivid illustration: Christ was eclipsed by incentives of conquest.

Colonialism and Empire

From the 15th century onward, Christianity was invoked to justify colonization. “Christian missions” were sometimes a fig leaf for resource extraction, conquest, or slavery. Colonized peoples were often dehumanized, their subjugation rationalized as a “civilizing mission.” In such cases, the gospel’s ontology was lost, and what remained was a baptized ideology of empire.

Mixed Outcomes, Misaligned Motives

It is true that positive fruits sometimes emerged: schools, hospitals, abolition movements, cultural uplift. But the goodness of some results does not justify the initial misalignment of motives. To confuse secondary goods with primary ontology is itself part of the problem. The apostles were not strategizing empires or crusades; they were bearing witness to Christ, often at the cost of their lives.

Why This Matters

This history illustrates the precise danger of Christian nationalism today, as well as of liberal Christianity. When the faith is fused with political incentives — whether throne, empire, crusade, colony, or ideology — it ceases to function as Christianity in the ontological sense. It behaves like every other naturalistic system we have tested: aligned with status games, coercion, and institutional patronage, not with the scandal of the Cross or the antifragility of persecuted witness.

The historical record therefore confirms what our model predicts:

- Christianity as ontology is antifragile under persecution and irrational by worldly incentives.

- Christianity as ideology is explained fully by naturalistic diffusion — gaining social power but losing the truth worth dying for.

3.5. Apostolic Witness as Empirical Reality

The unified test framework doesn’t merely suggest that Christianity is plausible. Its logic demonstrates, beyond rational doubt, that the apostles really did encounter the resurrection. Their behavior cannot be explained by delusion, hallucination, or myth. It is best explained by an encounter with ontological reality itself.

From “Foolishness” to Empirical Witness

The apostles were not proclaiming an idea calculated to impress their world. Their message was anti-memetic: a crucified God who defers vengeance and calls His followers to endure shame. By every sociological metric, this should have been a fragile, laughable claim. Yet they persisted at maximal cost. Game theory shows this persistence was irrational unless they had experienced something that redefined reality itself.

Not Delusion, but Encounter

Could they have been maximally deluded? No:

- Delusion breaks down under persecution. Groups fracture, stories diverge, enthusiasm wanes.

- Apostolic testimony held steady across decades, geographies, and brutal costs.

- Their willingness to die does not prove sincerity alone; what makes their testimony unique is that their God was proclaimed as foolish by their culture. To persist in proclaiming Him required more than sincerity — it required that they had seen.

Thus, their testimony was not “religious enthusiasm” or cultural myth-making. It was empirical witness to something they knew had happened.

Miracles as Secondary Testimony

The apostles also claimed to perform miracles. These were not ends in themselves but secondary testimonial artifacts. To outsiders, they functioned as confirmation that the apostles were not simply insane zealots. Their proclamation was anchored in reality, and the miraculous works were extensions of that same reality breaking into the lives of others.

In this way, what was anti-mimetic became mimetic:

- What was foolishness became wisdom — because reality itself endorsed it.

- What was fragile became antifragile — because the truth they carried could not be extinguished by persecution.

- What was a private encounter became communal — because the miracles allowed others to share in the same ontological rupture the apostles themselves had experienced.

Collapse of Epistemology into Ontology

For the apostles, their witness was not speculative philosophy. It was the collapse of epistemology into ontology. Truth was not an abstraction; it was a person. Their experience of the risen Christ was not “belief” in the modern, tentative sense. It was knowledge — grounded in objective reality that overwhelmed every alternative hypothesis.

This is why they could live as they did. Their witness was not an ideology to be negotiated but an encounter with the living God. And this is what Christians today often abandon when they trade the scandal of the Cross for the security of nationalism or the respectability of liberal politics. They give up the empirical, ontological center — the person of Christ — and settle for status games.

4. Techno-Eschatology, Antichrist, and the Counterfeit of Truth

Truth is ontological and personal. But our age is also witnessing the rise of a rival eschatology, one that seeks transcendence through technology. Peter Thiel’s recent private reflections on the Antichrist are symptomatic of this wider temptation — an acknowledgment that the end is possibly near, yet a misinterpretation of what the end is.

4.1 Thiel’s Techno-Eschatology

The instinct behind Thiel’s eschatological framing is not cynicism but seriousness: history has a telos; modernity is not a drift but a countdown; the human longing for consummation is real, and our era’s instruments—capital, computation, coordination—are not morally inert. In that sense, the “tech eschaton” begins with recognizably Christian nerves: an impatience with stagnation masquerading as wisdom, a refusal to baptize decay as prudence, a belief that matter and time can be disciplined toward glory. Even the Antichrist motif, in its best light, is a warning against counterfeit transcendence precisely because true transcendence exists.

But when this zeal slips its moorings from the living Christ and is re-anchored in human foresight and institutional cunning, it curves into reaction. The motive is to honor destiny; the motion becomes to manage it. Instead of receiving the kingdom as gift, we attempt to route around the Cross with program. The grammar changes almost unnoticed: from “Thy kingdom come” to “Our roadmap ships.” Providence is recoded as progress; covenant becomes capitalization; parousia collapses into product cycles and policy wins. The danger is not that the analysis is alert to evil—it should be; it is that the remedy slides from worship to will, from repentance to strategy, from sacrament to stack.

Once unmoored, three substitutions follow. First, ontology yields to instrumentality: the question “What is man that You are mindful of him?” is displaced by “What can man become if we optimize him?” Second, judgment yields to curation: sin becomes misalignment, rebellion becomes non-compliance, the fear of the Lord is replaced by risk frameworks, and “safety” stands in for holiness without ever naming a holy One. Third, hope yields to horizon management: the blessed hope is discretized into milestones; resurrection is tacitly traded for indefinite life-extension; new creation thins into a greener, wealthier, longer now.

Ironically, the Antichrist frame itself can become reactionary fuel. Seeing that the age is ripe for a counterfeit, we are tempted to preempt it by building a righteous counter-stack—money, media, medicine, machine—convinced that if the wrong priests will digitize the liturgy, the right priests must digitize it first. But rivalry with a counterfeit still concedes the counterfeit’s rule set. It fights Babel by out-engineering the ziggurat. It mistakes vigilance for vocation and forgets that the church’s first politics are baptismal and eucharistic before they are institutional and financial. In this sense, techno-eschatology from the right and techno-progress from the left are estranged brothers: both translate salvation into coordination, both enthrone elite operators as temporal custodians of meaning, both treat transcendence as a throughput problem.

None of this is an argument for quietism. It is an argument for re-mooring. If Christ is the telos of history, then history is not a blank canvas for the most competent coalition; it is a vineyard leased to stewards who will give an account. Under that ontology, venture becomes venture-as-vow. We build, but as penitent builders who know our towers cannot touch heaven. We invest, but as men and women who expect the Lord to return and ask about widows and weights and wages, not only throughput and TAM. We research, but as those who confess that truth is first Someone we meet, not something we mint.

Re-centered this way, the Antichrist warning regains its apostolic edge. It is not primarily a call to outpace a rival architect, but to refuse the oldest bargain: glory without Golgotha, crowns without thorns, power without prayer. The church’s counter-eschatology is not a better flywheel; it is the life of a people whose holiness and kindness—truth and mercy together—make an unseen kingdom visible now. Their technology serves persons rather than re-defining them. Their capital serves covenant rather than replacing it. Their governance serves neighbor love rather than disciplining the world into an aesthetic. And their hope refuses to be flattened into any horizon short of the appearing of the Lord, when the dead are raised and the world is judged and healed—events no product roadmap, however brilliant, can schedule or secure.

4.2 Techno-Transcendence as Counterfeit

Tech dreams do not begin in malice. They begin in mercy and wonder. A surgeon who wants brain–computer interfaces to restore speech after a stroke is moved by compassion. An engineer who chases abundant clean energy wants to hush the groan of creation. A coder who imagines AI tutoring for every child is reaching for justice. These are recognizably Christian longings—healing, liberation, illumination—because the world really is broken and we really do ache for its repair.

But when these longings slip their moorings from the living Christ and become a program for salvation by technique, the motive curves back on itself. What began as service turns reactionary: a bid to answer death with control, finitude with scale, sin with optimization. The pain is real; the response becomes a project to outrun the cross.

Unmoored, techno-transcendence reframes the human problem as latency, bandwidth, and compute. If the body fails, we will augment it. If the mind falters, we will scaffold it. If scarcity bites, we will automate it away. The metaphysic beneath the code quietly hardens: persons become processes; meaning becomes data; destiny becomes an engineering roadmap. Mercy collapses into management. Hope collapses into growth curves. Eschatology collapses into product cycles.

The anthropology follows. A person is treated as upgradeable hardware; community, as a network transport for incentives; history, as a curve to be bent by capital and code. Suffering is recast as a coordination failure, not a summons to communion with the Crucified. Death is a bug, not an enemy already defeated in a resurrection that cannot be shipped or scaled. Even when the rhetoric borrows biblical notes—light, new creation, a world without tears—the melody resolves in human mastery, not divine mercy.

The politics fall in line. If salvation is technique, then authority belongs to those who can build and deploy it. Stewardship becomes stewardship-plus-sovereignty; guardianship becomes governance. The cathedral moves into the datacenter; liturgies become launches; sacraments give way to subscriptions. We create a priesthood of operators and an order of catechumens who wait for access. The poor receive features, not fellowship. The sinner receives terms of service, not absolution. The lonely receive infinite connection, not a hand on the shoulder and bread broken in a room where someone knows their name.

All of this is reaction, not revelation. It reacts to the scandal of our limits by refusing them. It reacts to the ache for transcendence by simulating it. It reacts to the fear of judgment by promising curation. It reacts to the terror of death by vowing indefinite deferral. But a curated world is not a cleansed one, an upgraded body is not a resurrected one, and a delayed funeral is not a conquered grave. Technique can rearrange the furniture of the house; it cannot rebuild the foundation it sits on.

The result is a hollow praxis that behaves like any other ideology: tribes coalesce around stacks and standards; belonging is signaled by vocabulary and access; dissent is pathologized as “slowing progress.” Even virtues are instrumentalized. “Safety” becomes runway management. “Alignment” becomes compliance. “Beneficence” becomes a brand pillar. We inherit the moral language of the gospel while evacuating its ontological center—God with us, crucified and risen, Lord of time and matter.

4.3 The Twin Temptations: Christian Nationalism and Christian Liberalism

If techno-eschatology promises transcendence by code and capital, the church faces two homegrown counterfeits that promise renewal by politics. They are rivals in rhetoric yet twins in method: each trades Christianity’s ontological center—Jesus Christ crucified and risen—for a program aimed at managing history. Both ask the church to become an instrument of power rather than a witness to truth.

Christian nationalism seeks to fuse covenantal loyalty to Christ with civil authority and national identity. It treats the state as guarantor of Christian ends, sanctifying the levers of law, patronage, and coercion as the ordinary means of discipleship. In practice, it collapses the scandal of the Cross into the glory of the nation: weakness is replaced by sovereignty; enemy-love by bloc discipline; holiness by cultural dominance. The church becomes a tribe among tribes, her sacraments sublimated into the rites of civic belonging. On our unified test, its spread is explained by incentives and patronage: it thrives when political power rewards participation and withers when costs rise. That is ideology’s signature, not ontology’s.

Christian liberalism performs the same inversion from the other pole. It reframes the faith as a moral engine for progressive society—salvation retold as inclusion, sanctification as policy improvement, eschatology as the arc of history bending toward justice. Its public witness often champions genuinely Christian goods—mercy to the poor, dignity for the weak, hospitality to the stranger—but the center of gravity drifts from the crucified and risen Lord to the civic horizon of liberal democracy. Doctrine becomes negotiable where it jars with that horizon; sin is psychologized, repentance becomes therapeutic, and forgiveness is displaced by activism. On our test, this too is naturalistic diffusion: it scales by cultural respectability and institutional alignment, not by antifragility under persecution. It wins approval where the zeitgeist approves and trims truth where the zeitgeist rebels.

Both movements, in different keys, mistake instruments for ends. They turn the church from a people gathered around the presence of Christ into a coalition organized around outcomes. In nationalism, the outcome is order secured by sovereignty; in liberalism, the outcome is equity secured by reform. But Christianity’s offense does not come from managing outcomes. It comes from the invasion of Reality Himself—judgment and mercy arriving in a crucified God who rises, forgives enemies, and calls a people to die and live with Him. That ontological rupture generates a social ethic, yes—but the ethic flows from the Person. Reverse the flow and the church becomes an NGO with sacraments or a party with hymns.

The apostolic pattern exposes both counterfeits. The first believers did not seize power to impose holiness, nor did they baptize the empire’s ideals to gain prestige. They confessed a Lord the world called foolish, bore the costs their confession imposed, and created a community whose life—repentance, reconciled enemies, shared burdens, fearless hope—made an unseen kingdom visible. Where they had power, they used it as borrowed stewardship; where they had none, they suffered without hatred. In both cases the same ontology governed: Jesus is Lord. That center disciplines every praxis. It frees the church to act justly without worshiping justice, to love the nation without deifying it, to pursue good laws without imagining law can raise the dead.

To name the difference plainly: Christian nationalism and Christian liberalism both preach a gospel of progress—one by sovereignty, the other by inclusion. Christianity preaches a gospel of resurrection. Only one of these can carry the weight of the world.

When Good Motives Go Reactionary: Holiness without Christ, Kindness without Christ

Both projects are born of impulses the gospel itself affirms. The conservative instinct prizes holiness: a people set apart, faithful to God’s commands, unashamed of moral clarity in an age of confusion. The liberal instinct prizes kindness: the outstretched hand, the defense of the weak, the refusal to pass by on the other side. These are not alien to Christianity; they are its fruit. “Be holy, for I am holy.” “Blessed are the merciful.” The trouble is not the motive; it is the moment those goods slip their moorings from the living Christ and harden into programs that define themselves against an enemy.

Unmoored holiness becomes reaction. It drifts from participation in Christ’s life to anxious boundary-policing. The aim shifts from becoming like Jesus to securing a moral perimeter. Discipline turns punitive, repentance becomes performance for one’s in-group, and truth is wielded like a cudgel. The Cross, instead of naming our universal guilt and common need, is tacitly reassigned to “them.” The result is a culture of purity signals and power blocs—anxiety with a Bible verse attached.

Unmoored kindness likewise becomes reaction. It slides from charity anchored in the Truth who judges and saves into inclusion enforced by sentiment. Mercy decoupled from repentance turns therapeutic; forgiveness is displaced by affirmation; justice dilutes into activism that cannot name sin without losing social oxygen. To keep the coalition intact, doctrine is thinned to platitudes, and the Cross is recast as generalized empathy. The result is a culture of compassion signals and institutional gatekeeping—anxious friendliness with a halo.

In both cases, what began as obedience becomes a tribal identity. Holiness, abstracted from union with Christ, produces a moral nation with sharp borders. Kindness, abstracted from union with Christ, produces a moral agora with fuzzy borders. Each defines itself over against the other, and the rivalry hardens them both. The conservative becomes “holy” by not being like the lax; the liberal becomes “kind” by not being like the harsh. Enmity supplies energy. The church becomes a reaction machine.

This is why the outcomes converge, despite opposite rhetoric: hollow cultural praxis, ideological tribe formation, and a Christianity that behaves like any other naturalistic system. Reaction manufactures momentum, but it cannot manufacture life. It can enforce conformity or curate empathy, but it cannot raise the dead. Only Christ can do that—“the power of God unto salvation,” not the power of program unto alignment.

The cure is not to split the difference; it is to re-moor both goods in the One from whom they proceed. In Him, holiness is not a perimeter but a presence: the Father consecrating a people by the Spirit to resemble the Son. Church discipline becomes restorative, not performative, because its telos is communion. In Him, kindness is not sentiment but cruciform love: mercy that tells the truth, hospitality that refuses flattery, solidarity that bears a cross. Almsgiving is paired with proclamation; welcome is paired with repentance; justice is paired with judgment day. Grace and truth arrive together because they are a person.

Re-centered this way, the church stops living against an enemy and starts living before a Lord. Holiness is no longer a badge; it is a brightness that exposes and heals. Kindness is no longer a brand; it is a costly nearness that suffers and restores. And the tribal energies that feed our age—those mimetic surges of scorn, panic, and applause—lose their enthrallment, because the center of gravity has shifted from our projects back to His presence. Holiness is fulfilled; kindness is fulfilled; and neither becomes a counterfeit—because both are once again the overflow of Christ, not substitutes for Him.

4.4 The Apostolic Contrast

The apostles did not inherit a stable world or a flattering place in it. They faced a pagan empire proud of its power, a cultured elite confident in its wisdom, and religious parties certain of their rectitude. Their answer was not counter-empire, counter-elite, or counter-party; it was a counter-people—men and women gathered around a living Lord who had died and risen, and whose presence reordered everything they touched. That is the contrast our moment needs: not a quicker machine or a better program, but a different kind of people.

Re-moored to Christ, holiness is not a perimeter to defend but a presence to dwell in. It does not posture; it purifies. It makes communities where sin is named without theater, discipline restores rather than humiliates, oaths are kept without loopholes, marriages hold, and speech becomes clean because the tongue has been tamed by worship. Such holiness is unhurried and unafraid. It is not triggered by the failures of the age; it is animated by the nearness of God.

Re-moored to Christ, kindness is not a brand but a cruciform nearness. It refuses the soft contempt of performative empathy and the hard contempt of ideological sorting. It moves toward enemies without lying about evil, carries burdens without advertising them, gives alms without buying influence, and tells the truth without withdrawing love. It is not allergic to repentance or allergic to justice, because it knows both flow from the same wounded side.

Placed back in their proper order, holiness and kindness generate a social economy that no ideology can counterfeit. The church becomes recognizably other: debts are forgiven in fact, not merely in metaphor; quarrels end at the Lord’s Table because the same bread shames our pride; the poor are not a project but members whose lack is our lack; leaders carry crosses before they carry titles; the young learn to honor the old; the strong learn to take the lowest seat; and promises, once spoken, become bonds. These are not tactics. They are sacraments extended into ordinary time: baptismal dying-and-rising enacted in budgets, calendars, and kitchens; eucharistic communion enacted in reconciled friendships and shared roofs.

Such a people can use tools without becoming tools, build institutions without becoming institutionalized, and enter politics without turning the church into a party. They can adopt technology as artisans rather than evangelists, policies as penitent stewards rather than saviors, strategies as offerings rather than ultimatums. Because their future is secured by a resurrection, they are free to lose in history without despair and to win in history without idolatry.

This is why the apostolic pattern outlives every “this-worldly” salvation scheme. It is not reaction but revelation—life from the dead creating a culture of patience in an age of panic, truth in an age of spin, forgiveness in an age of scores, endurance in an age of fatigue, chastity in an age of appetite, generosity in an age of extraction, courage in an age of caution. A church like this does not need a ziggurat of power or an algorithm of influence. She needs her Lord—and when she has Him, the world sees a kingdom it cannot explain and a hope it cannot manufacture.

The contrast, then, is simple to say and costly to live: programs manage outcomes; the apostles bore a Presence. Programs can align behavior; Presence makes new creatures. Programs sort tribes; Presence reconciles enemies. Programs promise progress; Presence promises a Person—and with Him, judgment and mercy, now and at the end. Only that can carry the weight of history. Only that can save.

5. Beyond Frameworks: The Lord Who Won’t Fit Our Boxes

Christianity cannot be captured by a partisan dialectic or domesticated by a single framework. It is not the chaplaincy of a worldview. It is the announcement that Jesus Christ died for the Father, rose for our salvation, and in rising revealed His universal Lordship over all creation. That Lordship outruns time and place, party and nation. In Him, ontology, epistemology, and teleology meet: He is the ground of reality, He reveals the truth of reality, and He is the goal toward which reality moves. Every tribal script buckles before a Lord who is not our mascot but our Maker.

Why do we miss this? Because we keep Him at a safe distance—Lord in the abstract. Abstraction lets the tribe supply the content: holiness as our badge, kindness as our brand, technology as our ladder, politics as our refuge. Faith still saves; baptism still names us; but misalignment sets in. We say “Jesus is Lord,” then let the status game define what “Lord” must mean.

Clarity returns when we stand where the apostles stood—when Christ is not a concept but a person they touched. Consider what reordered their world:

- After crucifixion, they handled a living body: wounds offered to Thomas, fish eaten on a shore, bread broken by pierced hands. Death was not reframed; it was defeated.

- They watched Him ascend: authority relocated from Caesar’s palace to the right hand of God. Power was not seized; it was bestowed.

- Scripture ignited: the Law, Prophets, and Psalms opened like a vault. What had been sacred text became God’s testimony to the Son—promise recognized as fulfillment, shadow clarified by substance.

- Priorities inverted: trades left, inheritances risked, futures re-budgeted. Suffering changed valence; martyrdom ceased to be failure. Costly persistence stopped being irrational and became inevitable.

- A new people formed: fishermen and tax collectors, elite and enslaved, widows and magistrates—divided incentives, one allegiance. The centrifugal forces of status and tribe met a stronger center and held.

No wonder John reached for the word Logos. He wasn’t baptizing Greek philosophy; he was naming the shock: the Mind behind all minds, the Meaning behind all meanings, stood in front of him—and then stood up from a grave. Epistemology collapsed into ontology because Truth had a voice, hands, scars.

Seen from there, the claims of this essay come into focus:

- Programs—nationalist, liberal, or technocratic—cannot bear the weight of salvation. Presence can.

- Holiness and kindness flourish only when reattached to their source. Presence first, praxis second.

- Technology serves when desacralized, politics blesses when de-idolized, media speaks truth when tethered to mercy. Presence disciplines power.

- Attention itself is healed: the unseen and ongoing (Nigeria, the DRC, the ordinary neighbor) matter because the Lord of glory attends to sparrows and names the poor “blessed.” Presence heals vision.

So the church’s task is not to perfect a framework but to abide a Person. In Him the ontological center holds; in Him the epistemological light returns; in Him the telos is secured. The result is not withdrawal but a different engagement: tools used without worship, laws sought without savior-complex, enemies loved without naïveté, victims defended without retribution’s intoxication, grief transfigured without denial.

All tribalisms collapse with Him—not because He erases difference, but because He re-centers all things in Himself. “From Him and through Him and to Him are all things.” That is the only center large enough for the world we actually inhabit and the only hope bright enough for the deaths we actually face.

Choose your center. Presence or program. A crucified-and-risen Lord—or the latest machine, movement, or myth. Only one of these has walked out of a tomb. Only one can carry the weight of history. Only one can save.

6. In Conclusion

We return to where we began...

A man was shot on a university campus. A wife told her husband's killer “I forgive him.” Commentators chose teams. The timeline surged and split. Meanwhile, far from Western cameras, believers in Nigeria and the Congo buried their dead again—pastors, mothers, sons—faithful people whose names rarely trend. And the feeds kept asking us to pick: party or program, stack or strategy, slogan or scorn.

The thesis of this essay is that none of those choices can carry the weight of what happened—there or here. Because the gospel is not a program. It is a Person.

If Jesus Christ is risen and reigning, then Erika’s forgiveness is not sentiment; it is sane. Justice still proceeds; mercy is not amnesia. But vengeance is disarmed because a higher court is already in session. If Jesus is Lord, then the martyrs are not statistics; they are witnesses—our teachers. Their graves are not endpoints; they are seeds. If Jesus is Lord, then our media storms are unmasked as weather, not weather-makers; the climate of meaning is set elsewhere. If Jesus is Lord, then nationalism and liberalism, code and capital, can be received as tools—but only when they are stripped of their altars.

So what do we do now?

- We name evil without theatre, insisting on the truth of what happened in Utah and what keeps happening in Jos, Kaduna, Beni, and Goma—then we refuse to turn grief into fuel.

- We pray and act for the persecuted like kin, not content: intercession, money, advocacy, hospitality for the displaced; attention that outlasts the news cycle.

- We seek just laws and safer streets without pretending law can raise the dead—or that power can sanctify a people.

- We use technology as artisans, not evangelists: to serve specific neighbors, not to simulate transcendence.

- We practice a church-shaped politics: repentance before rhetoric, bread before branding, reconciled enemies before viral victories.

This is not withdrawal. It is re-centering. The center is not a tribe or a theory. It is a table where enemies become siblings because a crucified Lord is alive and presiding. From that Presence, holiness and kindness stop being banners and become a way of life. From that Presence, attention heals: the famous murder and the forgotten massacre belong inside the same prayer, the same fast, the same offering plate.

Charlie Kirk’s death demands justice; his wife’s words demand wonder. The martyrs of Nigeria, Congo, and elsewhere demand remembrance; their hope demands imitation. Our cultural chaos demands clarity; the gospel demands a different center. And the center holds—because it is not an idea, but a person with scars.

Choose your center. Then live like it.

A Testable Claim

This is not homily posing as analysis. It is a claim that survives contact with incentives, diffusion, and math. The framework treats every social system the same, fixes the scoring rules in advance, and then lets the game-theory mechanics (defect vs. costly persistence), the network signatures (patronage/coercion vs. antifragility under persecution), and the Bayesian update (likelihoods → Bayes factors → posterior) do the talking. You can review it, modify it, stress it with different priors or dependence penalties, and the direction of travel holds: the apostolic profile is stubbornly hard to model under naturalism and naturally explained if an extraordinary catalyst actually occurred.

This means the conclusion isn’t wishful thinking; it’s auditable. Change the priors; widen the error bars; penalize dependence between evidence nodes; run sensitivity analyses. The point isn’t to force agreement at the third decimal place; it’s to show that under fair play, Christianity’s evidential bundle keeps beating the baseline that explains ideologies, cults, and empire religions. Empiricism—soberly done—does not disqualify Jesus Christ; it drives toward Him. In fact, our social presuppositions often skew the science—smuggling in assumptions about what can’t be true and then calling the exclusion “method.” When those presuppositions are relaxed to let the data speak, the updates converge.

If you’re skeptical, good. Inspect the machine. Ask whether the early church’s antifragility is more probable on NAT or R. Ask whether adversarial conversion, mass-witness claims, creed stabilization, and the “anti-meme” of a crucified God are independent enough to stack, and then apply a dependence penalty. Ask what prior would be required to keep you under 50% after the update—and whether that prior is defensible before you look at the data. That’s not special pleading; that’s science done in public.

So the claim that Christianity cannot be collapsed into a tribe is not merely theological. It is empirical in the only sense that finally matters: the world as it actually behaved when confronted with Jesus Christ. Under shared rules and common math, Christianity functions like a universal constant—the one story whose weakness grows under pressure, whose truth keeps producing people who forgive enemies, bury their martyrs in hope, and refuse to worship the machines or the movements they can skillfully use.

You don’t have to start by believing. You can start by testing. Follow the incentives. Map the networks. Run the update. If reality is honest, it will take you where truth lives. And if the tomb is empty, the math will not save you from that discovery; it will deliver you to it.

So, we started off by talking about a murder and the question beneath it...Have we answered the question?

Yes, but by way of meandering across what in essence is the fracturedness of society today. The emptiness, the ideological factions--and why none of them provide any real meaning or healing or basis for existing; which for all intents and purposes is why sadly....an innocent man was shot.

His widow's reaction to this demonstrates the point of this essay...which is that even in the face of unimaginable pain, there's something more profound than life itself. If you do the math for yourself; you may see what she sees and know what she knows. That's the only reason I can think of for a widow forgiving her husbands killer...she's knows ontological Truth and that frames her posture towards what should be unforgivable actions.