The Settlement Trust Solution

Zambia has recently been experiencing over twenty hours of power cuts every day. Small businesses are stressed. Hospitals without emergency power can’t keep vaccines cold. Water pumps stand idle. Children study by candlelight. This isn’t a temporary inconvenience—it’s an economic emergency that makes 21st-century life impossible.

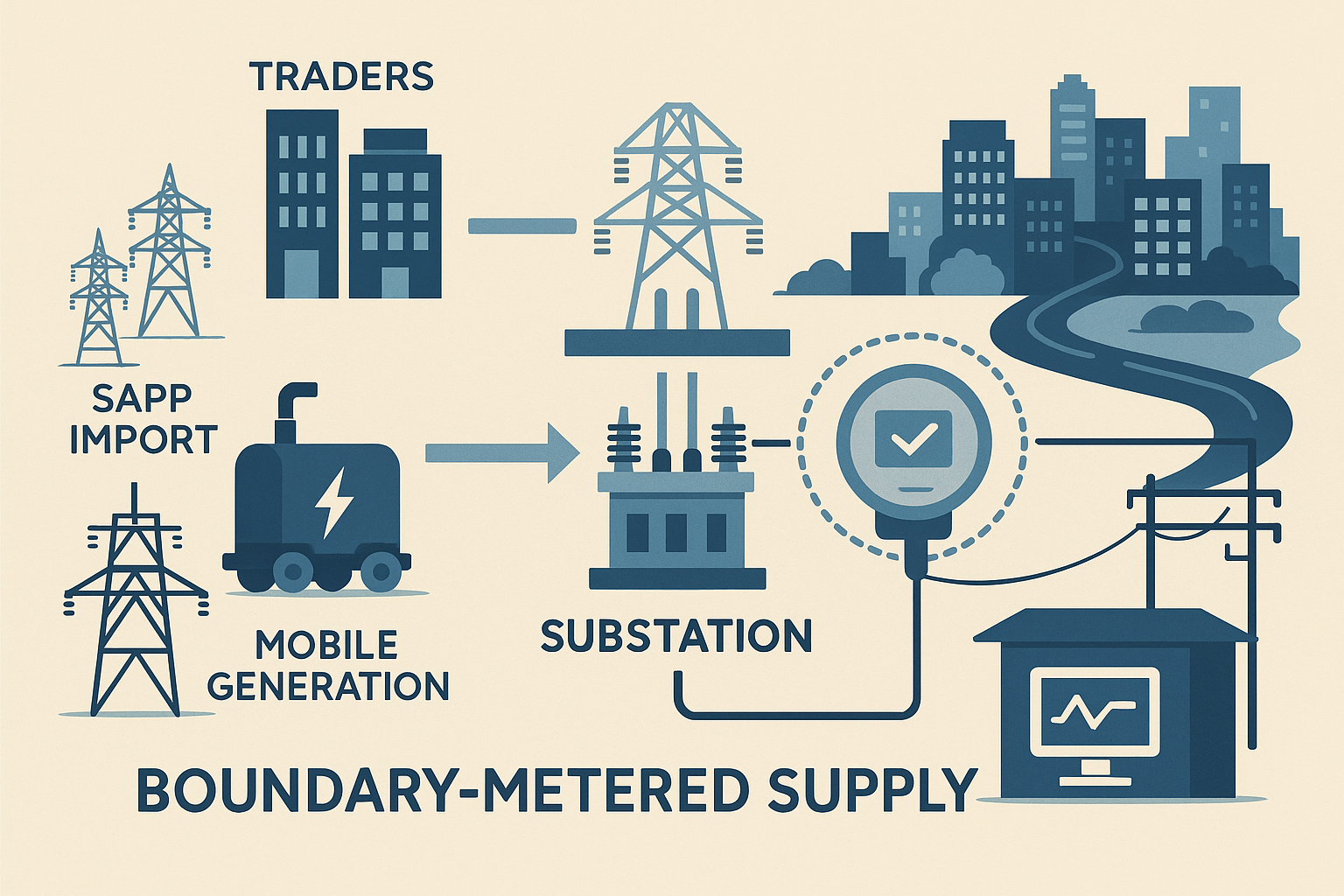

Everyone agrees we need more power. The physics is straightforward: Kariba and Kafue reservoirs are critically low, so we’re short roughly 700 to 1,000 megawatts of baseload generation. That power exists and is available—some neighbouring countries have surplus electricity in the regional power pool, and mobile generators can be deployed to substations or anchored as powerships. The electrons are there in principle—the issue is how to pay for them.

So what gives? Why isn’t ZESCO able to buy or import the power?

The Balance Sheet Problem

The answer lies not in physics but in accounting. ZESCO cannot borrow the money needed to import emergency power because its balance sheet is already strained. Commercial banks won’t lend without government guarantees, and creating those guarantees would expose taxpayers to risk and runs counter to the country’s fiscal posture at the moment—owing to debt restructuring and reform. The traditional model—where ZESCO borrows, buys power, sells it, and repays the loan—simply doesn’t work when the utility has no borrowing capacity left. ZESCO also has recent history of defaulting on power-purchase obligations—internationally (powerships) and locally (Maamba and Ndola Energy). It has been working through these legacy debts, but the shadow they cast still looms—and every citizen feels the darkness as a consequence.

However—here’s where it gets interesting. While ZESCO as an institution may be unbankable, ZESCO’s urban retail business is actually quite healthy. Nearly every urban customer has a prepaid meter. They buy electricity tokens before they consume power, which means real cash flows into the system every single day. These are customers desperate for reliable electricity who have already demonstrated they can and will pay for it.

The question becomes: can we use that existing cash flow—which is real money, already being collected—to pay for emergency power imports, without waiting for ZESCO’s balance sheet to be fixed?

The answer is yes, and the mechanism is simpler than you might think. Zambia has already proved that ring-fenced, bankable cash flows can unlock private capital without a sovereign guarantee. In May 2025, Kariba North Bank Extension Power Corporation (KNBEPC)—a ZESCO subsidiary—reached financial close on the 100 MW Chisamba Solar PV project, securing about $71.5 million from Stanbic/Standard Bank under a GreenCo PPA. The same discipline—clear offtake, segregated cash, and standard trade-finance instruments—can be applied to a retail surcharge trust that pays traders D+1 against boundary-metered deliveries.

Ring-Fencing the Solution

Imagine you run a struggling company with debt problems, but one division—let’s call it the Prepaid Division—generates strong daily cash. You can’t borrow against the company as a whole, but what if you could legally separate the Prepaid Division’s cash flow, put it into a locked account that your creditors can’t touch, and use that specific cash stream as security for new financing?

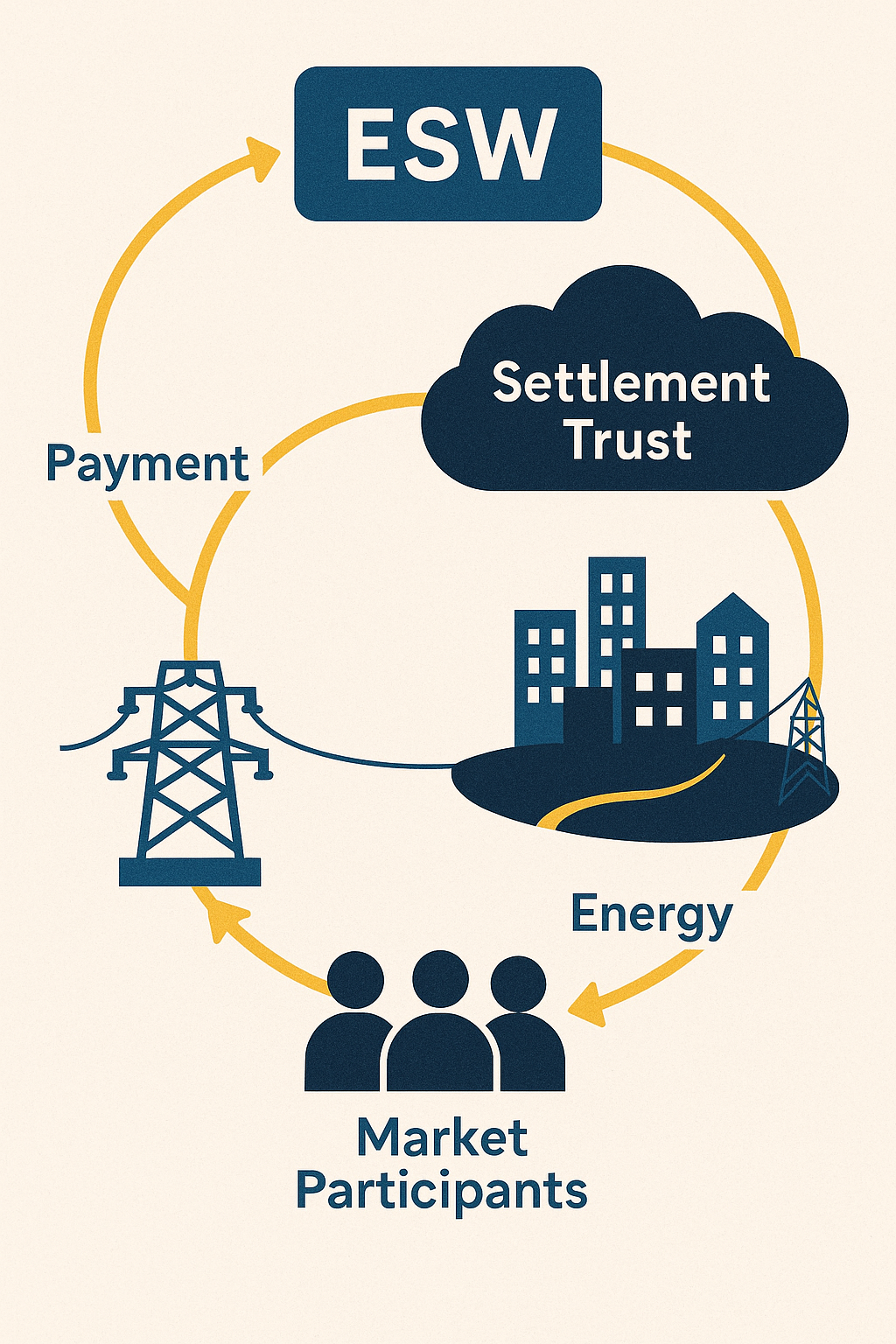

That’s essentially what I’m proposing for Zambia’s electricity crisis, with one important addition: we’re not asking ZESCO to do the borrowing at all. Instead, ZESCO or the government would invite creditworthy private power traders—companies that can independently borrow and have strong balance sheets—to import the power using their own credit lines. They get paid from the ring-fenced cash flow that urban customers are already generating through their prepaid purchases.

Here’s how it works in practice. The ERB would publish a simple formula each month: USD energy cost × FX rate (imports or mobile generation) + wheeling and ancillary services (Grid-Code items) + fixed technical loss factors + a capped non-technical-loss allowance + a small settlement/admin fee. All proceeds flow into a bank-administered Settlement Trust. Suppliers are paid only for verified injections at boundary meters (interconnectors or designated substations), net of approved loss factors and any imbalance penalties. This keeps physics and money aligned: you pay for what the grid actually receives. Think of it like a transparent fuel-adjustment charge—it covers the actual cost of importing emergency power during the crisis and it is published every month so everyone can see exactly what they’re paying for and why. The specific surcharge is a transparent pass-through of the cost of electrons at source + SAPP wheeling + a trader margin (financing cost plus fixed margin) + ZESCO charges.

This surcharge doesn’t go into ZESCO’s general accounts where it could get mixed up with operational costs or debt service. Instead, every kwacha collected flows directly into the Settlement Trust Account held at appointed commercial banks. That account has one job: pay for verified emergency power deliveries—nothing else.

Making It Bankable

Now comes the interesting part. Licensed power traders—regional electricity companies, rental-equipment firms, or power-trading specialists—sign delivery contracts to supply blocks of firm power for three to six months. They might import it through the Southern African Power Pool, or they might deploy mobile gas turbines at urban substations. Either way, they’re committing to deliver reliable electricity measured at specific boundary points in the grid.

But these traders need to pay their suppliers upfront. A regional utility selling power to Zambia wants US dollars today, not promises of kwacha next month. Fuel suppliers for mobile generators want the same. So the Settlement Bank uses the ring-fenced cash flow as security to issue letters of credit in US dollars to the traders. Those letters of credit allow traders to pay their suppliers with confidence.

Every day, the grid operator measures exactly how much power each trader delivered at the boundary meters—the interconnectors for imports, or the substations for mobile generation. That night, the Settlement Bank takes the day’s surcharge collections, runs the transparent payment formula, and the next morning the traders receive payment for verified deliveries. It’s a twenty-four-hour cycle: deliver power today, get paid tomorrow.

The bank keeps a reserve fund equal to seven to ten days of import payments in hard currency. This reserve serves two purposes: it gives traders confidence they’ll be paid even if there’s a brief collection hiccup; and, more importantly, it acts as an automatic brake. If that reserve starts running low—meaning customers aren’t paying enough to cover the imports—the system automatically pauses new power purchases until the balance recovers. This self-limiting feature is critical because it means the program cannot create debt or fiscal exposure. It can only operate within the bounds of what customers are actually paying.

The Forex Reality

One of the hardest problems in any Zambian trade transaction is foreign exchange. Regional power sellers want US dollars, but customers pay in kwacha. Exchange rates move daily, and getting dollars through official channels can be unpredictable. A poorly designed program would leave someone—either the traders or the government—exposed to crushing currency risk.

The solution has three layers. First, the Trust maintains its reserve fund in dollar equivalents, not kwacha, so there’s always hard currency available to pay suppliers. Second, the Trust uses forward contracts to lock in exchange rates thirty to sixty days ahead, removing day-to-day volatility risk. Third—and this is what makes foreign suppliers comfortable—the African Trade Insurance Agency or the World Bank’s MIGA provides a convertibility guarantee. This means that even if there were temporary restrictions on currency conversion, the guarantee ensures suppliers will still get their dollars. That guarantee isn’t a taxpayer liability because it’s backed by the actual prepaid cash flow, which is why no sovereign guarantee from the Zambian government is needed.

Dealing With Theft

Any honest conversation about electricity in Zambia has to acknowledge theft. Some customers bypass meters or tamper with them to steal power. That’s not theoretical—it’s a measurable problem that shows up in the gap between power ZESCO puts into the system and power it gets paid for.

Under normal circumstances, ZESCO absorbs those losses as an operational problem. But if we’re asking paying customers to fund an emergency surcharge, they have a right to demand that theft not be socialised onto them without limit. The design addresses this with a hard cap: the surcharge formula includes a non-technical-loss component that starts at twelve percent—roughly in line with recent audits—but that number is capped and must come down.

Every quarter, ZESCO has to demonstrate measurable progress in reducing theft. That means publishing numbers on meters audited, tampered connections disconnected, revenue recovered, and prosecutions filed. If ZESCO hits its targets, the theft component in the formula drops by one and a half percentage points per quarter. If theft exceeds the cap, ZESCO eats the excess cost—it doesn’t get passed through to customers via the surcharge. This creates a powerful incentive for ZESCO to get serious about revenue protection, because the better it performs, the more money flows to ZESCO from the residual at the bottom of the payment waterfall.

The public sees a monthly dashboard showing actual theft rates, enforcement actions taken, and how ZESCO is performing against targets. Transparency keeps everyone honest.

What Customers See

If you’re a residential customer using less than two hundred kilowatt-hours a month—roughly enough to run lights, a TV, a phone charger, and a small refrigerator—you pay zero surcharge. That lifeline exemption protects the poorest households from bearing the cost of emergency supply.

If you’re a household or business using more than that, you see a line item on your bill or prepaid token labeled “Emergency Energy Surcharge.” Let’s say the all-in rate works out to about five kwacha per kilowatt-hour. That’s higher than the normal tariff, yes. But here’s the comparison that matters: if you’re a business running a diesel generator to cope with load-shedding, you’re probably paying six-fifty to eight kwacha per kilowatt-hour when you factor in fuel, maintenance, and capital recovery on the generator. So even with the surcharge, grid power is still twenty to thirty percent cheaper than your current alternative.

Every month, the regulator publishes the formula showing exactly what you’re paying for: the cost of importing power in US dollars, the exchange rate, network charges for using ZESCO’s distribution system, technical losses on the grid, the capped theft component, balancing services from the grid operator, and a small admin fee for the Settlement Bank. Nothing is hidden. You can see that when import costs drop or the exchange rate improves, your surcharge drops too. And you can see it benchmarked against the diesel alternative so you know whether you’re getting value.

The trade-off is explicit: pay a transparent surcharge to get reliable power, or pay nothing extra and continue sitting in the dark for twenty hours a day while your diesel generator drains your bank account. For most businesses and urban households, that’s an easy choice.

No Government Guarantees

This is perhaps the most important feature of the entire design: the government’s balance sheet is not involved. There are no sovereign guarantees, no budget appropriations, no contingent liabilities, no debt assumptions. Cabinet’s role is simply to authorise the regulatory framework—letting ERB issue an emergency tariff order and establishing the Settlement Trust structure—and then step back while the system operates on a commercial basis.

If customers stop paying the surcharge, the Trust balance falls, the reserve fund depletes, and the system automatically curtails new power purchases before it can create losses. If the exchange rate moves sharply, the monthly formula passes that through transparently to customers or gets absorbed by the forward contracts the Trust already purchased. If a trader fails to deliver, they don’t get paid and face penalties under the Grid Code—but there’s no call on government funds.

This is fundamentally different from traditional power procurement where governments end up backstopping utility debt or underwriting currency risk. Here, the risk lives entirely within a closed commercial loop: customers pay for power before they consume it, that cash pays traders for verified deliveries, and if any link breaks, the system stops rather than creating a fiscal hole.

To keep things transparent and to ensure the lowest possible costs, the entire stack can clear through short, competitive auctions that optimise for low cost and high uptime. The goal is system resilience and the movement of electrons at prices everyone can justify and tolerate.

Speed and Governance

Under normal procurement rules, getting emergency power might take eighteen to twenty-four months. You’d need parliamentary approvals for guarantees, lengthy competitive tenders, complex financing negotiations, and inter-ministerial coordination that moves at bureaucratic pace. By the time power arrived, the crisis would have either resolved itself or destroyed the economy.

The Emergency Energy Surcharge model compresses that timeline to ninety to one hundred twenty days for first power by using emergency regulatory powers that already exist in the Electricity Act. ERB could issue time-boxed tariff orders that take effect within weeks. The Settlement Trust can use standard banking templates adapted for power-sector specifics. Trader contracts are short-form and reference the existing Grid Code rather than negotiating custom terms. And critically, because there are no sovereign guarantees, you avoid the entire parliamentary approval process for government debt.

To keep momentum, the President could chair a weekly thirty-minute scorecard meeting for the first ninety days—not to micromanage but to remove blockages in real time. When an inter-ministerial dispute that would normally take six weeks to resolve comes up, it gets decided in the room that week. When the Bank of Zambia needs to approve foreign-exchange allocations or customs needs to clear fuel imports, those decisions happen on a presidential timeline, not a bureaucratic one.

That political forcing function is what turns a clever policy design into operational reality. Without it, any one of a dozen chokepoints could kill the program through inertia.

What Success Looks Like

Imagine it’s a few months from now. Three hundred megawatts of firm power are flowing into Zambia. Some is imported through the interconnector from South Africa or Zimbabwe under bilateral contracts. Some comes from rental gas turbines installed at key substations. The grid operator submits daily nominations the evening before, the power flows the next day, boundary meters record the deliveries, and traders receive payment twenty-four hours later.

Urban businesses that were operating four hours a day are back to sixteen or eighteen hours. Hospitals have reliable power for cold storage and surgeries. Water utilities are pumping consistently. Telecom towers aren’t draining their backup batteries. Students can study after dark without burning through expensive candles or diesel. The specific neighbourhoods receiving the most stable power are published, so everyone knows which feeders are prioritised and why—typically areas with hospitals, water infrastructure, high commercial density, or where smart metering makes revenue collection most reliable.

On their phones or in newspapers, people see the monthly dashboard: how much power is being supplied, what it costs, how that cost breaks down, what the diesel alternative would cost, how many days of reserves the Trust holds, and how ZESCO is performing on theft reduction. When someone complains about the surcharge, the data is public and the benchmark is clear. When ZESCO gets serious about disconnecting meter-tamperers and the theft rate drops, everyone sees the cap come down and the surcharge decrease accordingly.

After nine months, the rainy season returns with force. Kariba and Kafue start refilling. Hydro generation recovers. The Emergency Tariff Order expires on schedule, the temporary surcharges disappear, and bills return to normal. The Settlement Trust pays out final invoices to traders and dissolves. But the infrastructure that remains is valuable: tested protocols for third-party power supply, transparent boundary-metered settlement, published loss factors by voltage level, and proof that Zambia can execute commercial power transactions on international terms when the governance is right.

Why This Works When Other Solutions Don’t

Development institutions and advisers have proposed many solutions to Zambia’s electricity crisis over the years. Build more generation capacity—true, but that takes five to ten years and billions in financing. Fix ZESCO’s balance sheet—critical for the long term, but that’s a multi-year reform program that won’t keep the lights on this quarter. Raise tariffs to cost-reflective levels—economically correct but politically explosive, and it still doesn’t solve ZESCO’s borrowing constraint in the near term.

The Emergency Energy Surcharge works because it doesn’t wait for any of those structural reforms to complete. It accepts ZESCO’s balance sheet as broken and routes around it. It accepts that the government can’t issue new guarantees and designs a structure that doesn’t need them. It accepts that normal procurement is too slow and uses emergency powers to compress the timeline. And it accepts that customers will only pay more if the value proposition is transparent and better than their alternatives. All the usual reforms should proceed—but between now and the completion of new power plants, people still need electricity.

Most importantly, it uses a resource that already exists but is currently misallocated: the daily prepaid cash flow from urban electricity customers. That flow is real, it’s substantial, and it represents customers who desperately want reliable power and have demonstrated ability to pay. By ring-fencing that specific cash stream and using it as security for creditworthy traders to import power, you unlock a solution that is simultaneously fiscally safe, operationally implementable, politically defensible, and genuinely fast.

The question was never whether the electrons exist or whether customers would pay for them. The question was whether we could design a structure that brought those two facts together safely. We can. The legal framework exists in the Electricity Act’s emergency provisions and the Electricity (Open Access) Regulations, 2024 — S.I. No. 40 of 2024. The financial mechanics are standard trade finance adapted for power. The technology is boundary metering and daily settlement that power markets around the world use routinely.

The Choice Ahead

Twenty-plus hours of daily load-shedding is unacceptable. It’s stressing businesses, forcing closures, driving away investment, and making ordinary life needlessly difficult. The longer it persists, the more permanent the economic damage becomes—and the more national morale is sapped by the lack of light.

This is a solution that could deliver two to three hundred megawatts within three months, and scale to five hundred megawatts by month four. It requires no taxpayer money, creates no government debt, and automatically prevents itself from becoming a fiscal problem. It’s transparent enough that citizens can verify they’re getting value and hold ZESCO accountable for theft reduction. And it builds the institutional foundations for competitive power markets that will serve Zambia well beyond this immediate crisis.

What it requires is a decision. Cabinet approval to authorise the regulatory instruments. Presidential leadership to drive execution speed and remove blockages. Regulatory courage from ERB to use its emergency powers decisively. Commercial discipline from the Settlement Bank to operate the waterfall and enforce the automatic brake. And public buy-in based on transparent communication about costs, benefits, and the temporary nature of the surcharge.

The technical work needs to be done for sure. This is just a blog post by a citizen. Nonetheless, the legal path is clear. The financial mechanics are bankable. The only question remaining is whether we will act with the speed the crisis demands. Zambia is literally in the dark. We know how to turn the lights back on. It’s time to flip the switch.